Blockade-Running During the War By Confederate Magazine

Posted By : manager-2

Posted : November 5, 2020

Running the Yankee Blockade:

A Daring Daytime Run by the Little Hattie

From Confederate Veteran magazine,

Volume VI. , No. 5, May, 1898, original title

“Incidents in Blockade-Running”

Signal-Officer Daniel Shepherd Stevenson has written for the archives of the Daughters of the Confederacy at Wilmington, N. C., a sketch, from which the following is taken:

In the soft, mild days of October, 1864, while we lingered at our cottage by the sea, on Confederate Point, I witnessed the most exciting and most interesting scene of my life. It was during dark nights that blockade-runners always made their trips, and the bar was shelled whenever one was expected. The “Little Hattie,” a blockade-runner, on which my nephew, D. S. Stevenson, was signal-officer, was expected, and the bar was vigorously shelled each night to keep the blockading fleet at a safe distance.

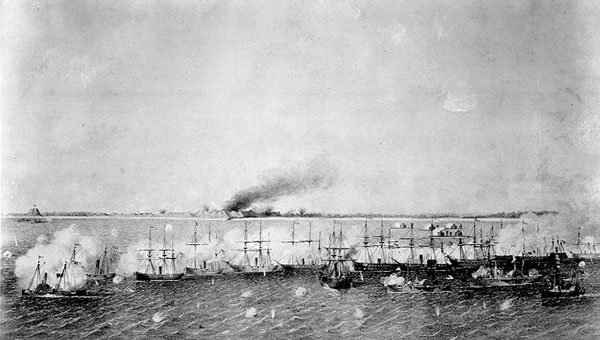

The SS Banshee. The Little Hattie probably looked like this.

Capt. Lebby, a dashing young South Carolinian, commander of the “Little Hattie,” had ordered the fires banked just at the dawning of the day, as they neared Cape Lookout, intending to wait until the next night, when he would run down the coast and come in through New Inlet at Fort Fisher; but before the order could be carried into effect he saw, by the movement on the Yankee fleet stationed off Cape Lookout, that his vessel had been discovered.

Immediately he rescinded the command, and, turning to Lieut. Clancey, first mate, and to Dan, said: “They see us, and I am afraid we shall be captured, but we will give them a lively race for it.” Then, turning to one of the men, he said: “Tell the engineer to crowd on the steam, have the fireman to feed the furnace with Nassau bacon, and we will make this run in broad daylight.”

The Captain then directed Clancey to run up the “fox and chicken” (the private flag of the “Little Hattie”), throw out the stars and bars, and fling to the breeze every inch of bunting on board, saying: “If we must die, we will die game.”

This map of the Union attack on Ft. Fisher in Jan. 1865 shows the route the Little Hattie would have taken.

The fires on the Yankee fleet had been banked before the “Little Hattie” was sighted, and it took some time to clear out the furnaces and raise steam. Thus the “Little Hattie” had some start of her enemies, and well she responded to her extra steam. Young Stevenson said that to his anxious mind it seemed that at every pulsation of her great iron heart her tough oaken sinews would quiver as though instinct with life, and she seemed to leap out of the water. Eight blockading steamers joined in the chase, and kept up a murderous shower of shot and shell.

The foregoing my nephew told me; what follows I witnessed.

About nine o’clock on that lovely October morning, when all nature smiled so kindly upon our war-desolated land, a courier rode up to our front door and shouted: “There is a blockade-runner coming this way and she looks like the ‘Little Hattie.'” The “Little Hattie” had two smoke-stacks.

I sprang to my feet, took some powerful field-glasses belonging to Maj. James M. Stevenson, stepped out on the roof of the porch facing the ocean, and looked. Sure enough, it was the “Little Hattie,” and, to my horror, I saw a figure on the paddle-box whom I knew to be Dan, with flag in hand, signaling to the fort.

The agonizing suspense of his mother could find vent only in prayer, and at a window looking toward the sea she knelt and supplicated the Throne of Mercy for her boy and his companions in danger. The shrill screeching of shot and shell was agonizing.

Onward dashed the frail little craft with eight United States steamers following close in her wake, pouring a relentless iron hail after her.

When she came near the fort the thirteen ships stationed off the mouth of the Cape Fear River joined in the fray, but He who “marks the sparrow’s fall” covered her with his hand, and not one of the death-bearing messengers touched the little boat.

The guns of the fort were manned, and shot and shell, grape and canister, both hot and cold, belched forth from the iron throats of Parrot, Columbiad, Whitworth, and mortar. This was done to prevent the fleet from forming on the bar and intercepting the entrance of the “Little Hattie.”

For nearly an hour I stood on the roof watching the exciting race, and when the “Little Hattie” came near enough to discern features, I recognized Capt. Lebby with his trumpet, Lieut. Clancey, with his spy-glass, and Dan, still standing on the paddle-box with his flag, which, having served its purpose for the time, rested idly in his hand.

Thus, at ten o’clock that cloudless October day, there was accomplished the most miraculous feat: a successful run of the blockade by daylight.

I give another incident in the blockading career of Signal-Officer Stevenson as received form him:

On the night of December 24, 1864, the same fatal year, the whole attacking fleet was lying before the fort when the “Little Hattie” came on her return trip. As they saw the congregated lights on the one side and the one lone light on the other, Capt. Lebby remarked that they had made the wrong inlet, and would have to come in on the high tide between Smithville and Bald Head, as they had passed Fort Fisher.

“No, Captain,” said young Stevenson; “we have not passed Fort Fisher. The many lights you call Smithville is the Yankee fleet, and the one light you call Bald Head is Fort Fisher Mound light.”

The captain and Lietu. Clancey laughed at him and pushed on, but he proved to be right. Fortunately, the night was very dark, and so many vessels were grouped together that one more was not noticed by the enemy. Before the officers of the “Little Hattie” were aware of it, they were in the midst of the fleet which bore Butler’s expedition against the fort.

Consternation seized them. Escape seemed impossible. But they had a trusty and fully competent pilot on board, Capt. Bob Grissom, who took his stand at the wheel-house, and Dan, at the word of command, mounted the paddle-box with his lantern, and signaled to the fort to let up the shelling until they could get in.

J. C. Stevenson, his brother, who was also a signal-operator, and on duty that night, reported that the “Little Hattie” was at the bar and asked that the shelling be stopped to let her in.

A test question was flashed to the boy on board, which, of course, he answered correctly, and the shelling ceased.

In and out the little craft wound among the vessels of the Yankee fleet so close at times that young Stevenson, as he stood on the paddle-box, could hear the officers as they gave commands, and see the men executing them; but again they were shielded “in the hollow of His hand,” and again made an almost miraculous escape. The next morning, December 25, as the fleet was shelling the fort, the “Little Hattie” steamed up to Wilmington and Dan walked in and gave us his perilous experience of the night before.

All know that the first expedition against Fort Fisher was unsuccessful, and when the siege was raised, the “Little Hattie” left this port, never to return.

How well I remember the last time I saw Capt. Lebby! I had been down the street, and had met and walked a few yards with him, bidding him good-by, for he was to sail in a few hours.

I crossed the street, and he called to me, and when I turned, he stood with hat in hand, making one of his most courtly bows, and said: “You and your sister must not forget the ‘Little Hattie’ at night and morning.”

We never did, until we knew that the dainty little craft and her perilous trips were ended.